When Terry Kawaja, founder of investment bank Luma Partners, stood on stage at the Association of National Advertisers’ annual Masters of Marketing conference last year and told a packed crowd that they should fire their CMOs, a challenge was set. Kawaja encouraged established giants such as Unilever and Procter & Gamble Co. to either adopt more direct-to-consumer strategies, or risk losing their lunch to the growing field of buzzy startups like Harry’s and Everlane.

Now, one year later, the landscape has changed. Big CPG brands are spawning a lot more d-to-c startups of their own. P&G has 180 of them, while L’Oreal has its own customized d-to-c hair coloring startup, Color & Co. Both are using their internal manufacturing and sales forces to help move the products faster into broader retail distribution. They’re also responding faster to threats from d-to-c startups and buying more of them.

The appeal for big marketers isn’t just sales.

“There’s a lot of value in going direct-to-consumer beyond just driving revenue,” says Jake Matthews, an intelligence analyst at CB Insights. “It’s creating a direct relationship with the customer which obviously has a lot of benefits—understanding the customer at a much more granular level, understanding their online behavior and getting a profile of the customer.”

At the same time, d-to-c players are increasingly resembling conventional retailers. They’re opening their own stores, or wholesaling in chains such as Target and Walmart. They’re spending big marketing bucks on TV ads and investing in full-scale brand campaigns rather than just relying on performance marketing to move the needle.

“Brands should have this one-on-one relationship with the customer,” says Andrea Hippeau, principal at Lerer Hippeau, the venture capital firm behind well-known retailers including Allbirds and Casper. “Consumers are looking for a lot more from brands now than ever before—you have to engage them at multiple touchpoints before they’ll make a purchasing decision and trust the brand.”

Hippeau recently told P&G’s internal Signal digital conference that her firm won’t even consider funding d-to-c startups that don’t have a plan to move into offline retail operations.

The changes from both sides come at a pivotal time. A recession might be looming, and retail experts expect shoppers to begin tightening their purse strings. While d-to-c brands were innovative and exciting a decade ago, the shine has worn off the model and consumers have come to expect more value from the companies they shop, whether in the form of loyalty programs, ease of shopping or brand purpose.

“Probably 10 years ago, when the fun started, we did our first investments in Warby Parker and we were investing in the innovation of the model,” says Hippeau. “Now, we’re looking for a more well-rounded brand … You need to be thinking a bit outside the box but have a more traditional mindset.”

Not a new concept

The buzz around d-to-c has been growing, in recent years, though the actual strategy of selling directly to customers is, of course, nothing new. Yet e-commerce made it easier to start a brand, and social media opened the door to stronger consumer relationships. Thus, digitally native brands, the modern iteration of d-to-c, have grown, according to Nate Checketts, co-founder and CEO of Rhone, a men’s sportswear brand that sells directly to customers and in places such as Peloton and Equinox.

“D-to-c has existed for a long time—it’s not a new concept that someone would sell directly to a customer, that’s existed for hundreds of years,” Checketts said recently at an Advertising Week panel, noting the “digitally native” distinction. “But with e-commerce, brands have unparalleled access to their customer and can scale those relationships much faster, as it was traditionally constrained by a retail geographic footprint.”

But things have gotten harder for d-to-c packaged-goods players on two fronts in the past couple years, says a veteran marketer of one prominent startup, who asked to not be identified.

The rising costs of Facebook and Instagram advertising, combined with the logistical costs of shipping, make it hard for a pure-play d-to-c player to be profitable, the marketer says. The added distribution and efficiency of selling through a Walmart or Target are necessary to push most of them into the black.

In that sense, the new generations of digital d-to-c players aren’t unlike the gadget and gizmo sellers of a prior generation of direct-response TV brands. Pure DRTV plays were rarely profitable, even at lower-than-primetime rates, unless that early exposure catapulted the brands into conventional retail distribution.

A close shave

Also, the days when d-to-c startups could run rings around big, slow-moving CPG incumbents and retailers are ending. The shaving razor business of the past eight years provides an illustration on both fronts.

Dollar Shave Club launched in 2012, and it took Procter & Gamble Co.’s giant incumbent Gillette years to react. Harry’s (since acquired by Schick marketer Edgewell) launched a year later, also d-to-c, and got off to a slow start. But once it entered Target and Walmart last year, Harry’s began picking up share on Dollar Shave Club, purchased in 2016 by Unilever.

Meanwhile, after fumbling with initial attempts for its own shave club, Gillette retooled to ditch the subscription model in favor of an “on demand” restocking. Through the first seven months of this year, online traffic to Harry’s was up 17 percent and to Gillette On Demand was up 4 percent. Dollar Shave’s traffic was down almost 19 percent during that time, according to Similarweb.

P&G wasn’t caught napping when the d-to-c battle shifted to women’s razors with the launch of upstart Billie in 2017. By last year, P&G, which markets category leader Venus, had prepped the launch of a new women’s shaving brand, Joy, priced and positioned similar to Billie, to be sold exclusively at Walmart—effectively blocking Billie from pulling a Harry’s-style maneuver into the biggest U.S. retailer. Billie, which launched two years ago, declined to comment.

Building up a stable

P&G also has begun cranking out a growing number of its own d-to-c startup brands across numerous categories, many new to the company. Among the 180 startups is one that has already graduated into conventional retail distribution.

Zevo, a P&G brand of plug-in bug zappers and insecticides using essential oils rather than synthetic chemicals, started small in 2017 with Facebook and Instagram advertising and direct-to-consumer distribution via Shopify. Zevo has been gradually building its business to the point of launching nationally in Home Depot and Amazon this year.

P&G has some advantages that smaller d-to-c startups don’t, including a large and often untapped pool of patented technology, its own plants that often can run small batches of startup brand products, and plenty of its own capital so that principals don’t have to spend so much time raising money. Then, if they do show enough promise, P&G has a sales force that can readily move them into conventional retailers.

Leigh Radford, VP and general manager of P&G Ventures, described the unit in a panel discussion at Cannes earlier this year as not an investing arm but “a studio, creating new brands for P&G” that’s largely internal, but also done with external entrepreneurs, in some cases through an incubator developed with Los Angeles venture firm M13. Once brands are created, some might be spun off into partnerships with outside CEOs, be sold or even go public, she says.

The idea is for the new brands to build much like outside d-to-c startups, learning as they go without getting big cash infusions up front, in the manner of traditional P&G launches, Radford says.

“What the direct-to-consumer avenue provides is that ability to create one-on-one relationships early on to co-create brands,” Radford says. “At P&G or Unilever, we kind of lost the consumer because they got further away from us. This allows us to come back and build brands, which we are really good at, with the consumer at the center.”

Big retailers haven’t missed out either on the fact that they can help directly spawn their own versions of d-to-c startups. Walmart earlier this year joined with Kirsten Bell and Dax Shepard to launch Hello Bello, a brand of plant-based personal care products that looks a lot like the Jessica Alba-

founded Honest Co. and is sold jointly by the couple through d-to-c and in Walmart stores.

Scaling with TV

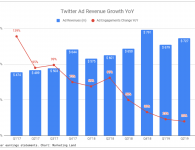

As larger marketers acquire d-to-c brands or launch their own, startups are branching into new marketing channels in order to scale their businesses. Since Instagram, Facebook and even subway ads—once viable options for starting a brand—have grown crowded and more expensive, many young brands are turning to TV. Indeed, in the first half of this year, d-to-c marketers grew their spend on TV by more than 50 percent compared with the year-earlier period, according to a recent report by Interpublic Group of Cos.’ Magna.

“You see these direct-to-consumer companies leveraging more mass marketing channels than they used to,” says Matthews. “They start to expand beyond the grassroots marketing they’ve been doing on a channel like Instagram; you start to see them utilizing more traditional means of reaching customers either through Google display advertising or TV.”

Brands such as Boll & Branch, a five-year-old seller of premium bedding products, have found TV to be an effective marketing channel when added to the digital mix. Scott Tannen, founder and CEO of Boll & Branch, recently told Ad Age that digital channels were “underpriced” but are now priced more “appropriately,” which adds to the clutter and lessens the effectiveness of such platforms.

Similarly, Bombas, a startup sock seller that donates a pair to the homeless for every pair it sells, also advertises on TV, though Facebook still represents 40 percent of the brand’s media spend, according to David Heath, co-founder and CEO of the five-year-old company.

“TV was a big unlock for us,” Heath said during Advertising Week. “You have to invest a lot and have a big budget, but surprisingly it has performed incredibly well.”

To that end, TV networks have been targeting d-to-c brands ready to make the leap to the

small screen. This year alone, Viacom, A&E and NBCUniversal have all rolled out the red carpet to

such brands by offering dedicated programs for d-to-c advertisers.

Digital brands have also ventured into the physical realm with their own stores or wholesale channels. In addition to its website, Dagne Dover, a functional bag purveyor, sells in its own pop-up store and at Nordstrom. Big-box retailers including Target are welcoming such companies with open arms. The Minneapolis-based chain bet big on d-to-c early on with Harry’s in 2016.

Now, the 1,800-unit Target has partnerships with brands including Native, Quip, Bark Box, Casper and Myro. Exclusively selling brands that are hard to find or online only helps give customers another reason to shop at Target, says Christina Hennington, senior VP-general merchandise manager of essentials, beauty, hardlines and services. She notes that the goal was “to continue increasing differentiation in our product assortment,” a strategy she says is playing out well for both Target and the digitally native brands it stocks.

“Brands have seen incremental growth and gained access to new customers, while we have the benefit of adding newness to our product assortment,” Hennington says.

Still plenty of challenges

Of course, several challenges remain for d-to-c brands that heritage players have already mastered. Critics say that several digital brands have zeroed in on young millennials in urban areas, but in the process, they’re ignoring huge swaths of the population, like older generations and Americans in the middle of the country. It’s a demographic the P&Gs of the world have already courted.

“There are a lot of brands big and small going after the 18-to-24 segment,” says Hippeau. “While that is sexy and they’re trendsetters and there’s a lot to be learned and gained from going after that segment, the fact is that older demographics are a lot more tech-savvy, and they’re mobile shoppers now.”

Strangely enough, one of the biggest threats to d-to-c startups might be getting drowned in the cradle by too much venture capital, says Shaun Neff, founder of Neff Headwear who has founded or advised a series of brands including Sun Bum suncare (sold earlier this year to SC Johnson), Kendall Jenner’s Moon oral beauty care brand, and merchandise brands for a variety of YouTube influencers such as James Charles.

“This idea of raising a ton of money with tech-level valuations and just literally burning through cash to acquire customers, I’m just not a fan of that,” Neff says. “That’s the big model that everyone is talking about in CPG and apparel recently. And there’s been a handful that have worked and luckily sold, but in my opinion that’s not a sustainable long-term model. You’re just spending a ton of money to acquire a customer rather than building an incredible brand people hear about from word-of-mouth.”

The newer brands Neff launches or helps launch generally start initially direct-to-consumer for a short time, as little as a month, with an idea of quickly moving into a conventional retailer, he says. “I love the idea of retail,” he says. “It brings credibility and eyeballs and high distribution to let people know you’re in the game.”

But with the d-to-c field growing crowded, and larger marketers looking more like d-to-c brands, experts say it will be harder for newer brands to differentiate. Many already resemble one another, by offering a mattress in a box, for example. If a problem for a consumer is already solved by an existing product from a brand that has an established base of loyal shoppers, consumers won’t be interested in a new startup selling a similar problem-solving item, says CB Insights’ Matthews.

“The most interesting thing to look out for moving forward,” Matthews says, “is how many of these d-to-c companies are going to survive.”

read more at https://adage.com/section/rss by Jack Neff, Adrianne Pasquarelli

Digital marketing